I think people who make videos and films are sometimes a little unclear about the relationship between 4K and HD. The most important message is this: that 4K is four times the data rate of HD, and you’ll need four times the space to see it.

But while there are four times as many pixels as HD, but the picture is not four times better. It’s actually only twice as good, if you measure the “goodness” of a picture by the number of pixels in a straight line.

Just to be completely clear about this, 4K has only twice the linear resolution of HD. This has some very important consequences.

Perhaps the most important of which is that if you degrade the sharpness of a 4K image by as little as just over half a pixel, you might as well have started in HD.

Half a pixel! That’s one eight thousandth of the width of the screen. You do’t have to have much wrong with your picture to lose its 4K-ness in an instant.

Remember that when we judge the sharpness of a picture, we’re not actually measuring it. What we’re absolutely not doing is counting pixels and how they merge with their neighbours. We base our impressions of sharpness on - impressions. We can be fooled into thinking that a picture is sharper than it is.

How does "sharpness" work?

Do you know how the “sharpness” control works in Photoshop? Well, I’m pretty sure that it’s evolved into something quite sophisticated, but the basic principle is rather simple. Our perception of how sharp an image is depends on edges. The more distinct edges we see, the sharper we think the picture is. When we sharpen a picture, we’re not adding information. How could we be? If adding information was that easy then I could just write half this article and move the "detail" slider another fifity percent and it would be finished!

What we’re doing is saying “whenever you see an element in the image that is changing more rapidly than the others, make it change even more rapidly".

Make it sharper, in other words.

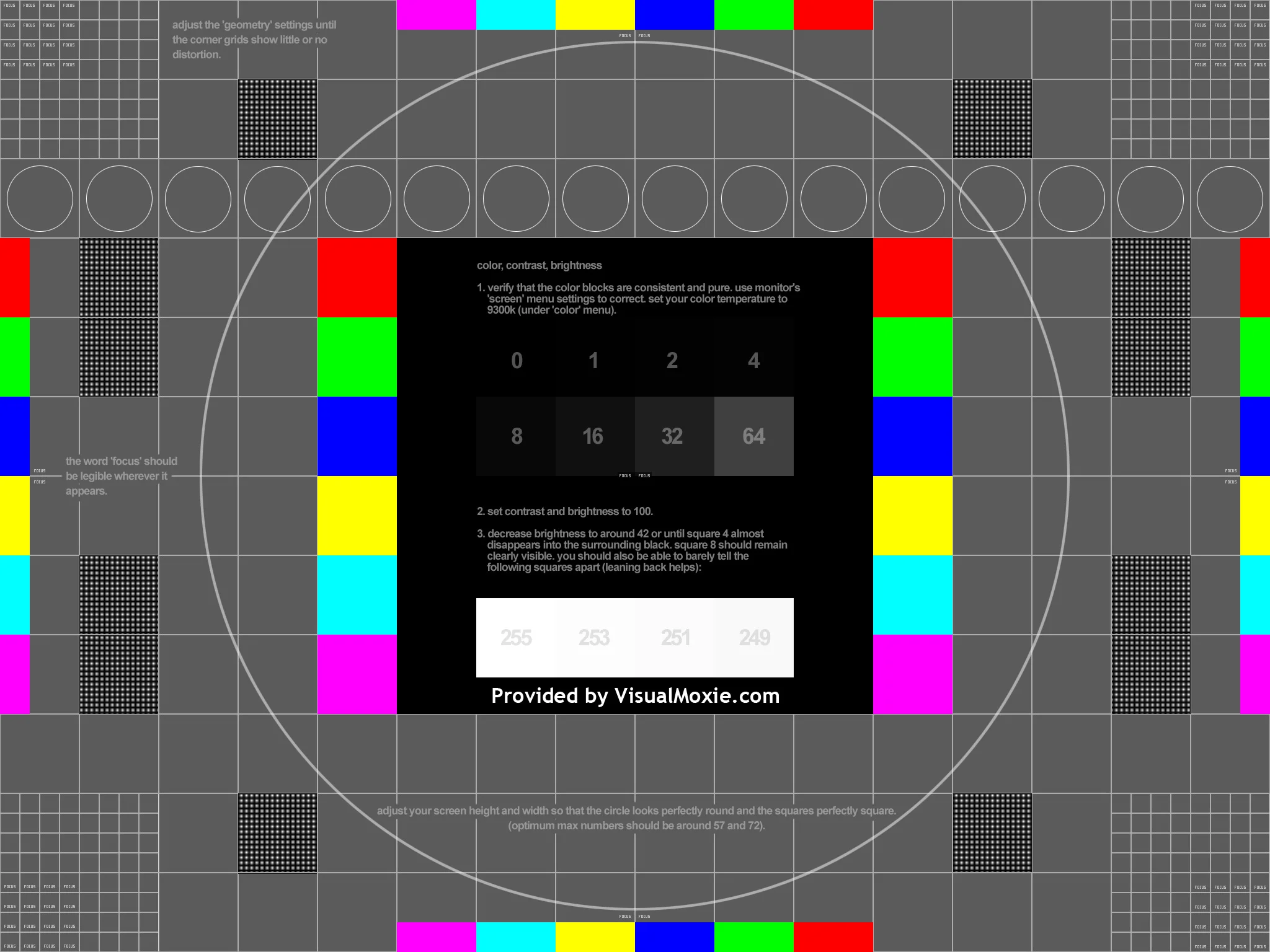

The sharpness of an image depends on frequency response. That probably sounds like it should be in an article about audio rather than video, but there’s really no difference. Think of a chessboard. If you were to scan a laser beam across the surface and measure the reflections, you’d essentially get no reflection from the black squares, and a 100% reflection from the white ones. When you move from black to white, the change should be instant, subject only to the width of the laser beam.

That instantaneous change represents a high frequency at that instant. Whether you actually see an instantaneous change depends on the ability of your recording, transmission and display system to reproduce it.

High frequencies mean more information. If you want to reproduce twice the frequency, then, in a digital system, you have to have twice the sample rate. That means twice the data. One of the easiest ways to reduce data rates is to limit high frequencies. In a sense, all you need to reduce your data rate by half or more is to introduce a low-pass filter (one that only lets lower frequencies through). Most recording, transmission and display systems do this anyway in the way that they handle the information and it’s certainly a fundamental aspect of the way that most codecs work.

Let’s go back to the chessboard. What’s the effect of filtering the high frequencies out? The edges between the squares look blurred. They look like that because there’s less information to describe exactly where they are. Remember: sharpness is all about information.

Artificially boosting high frequencies in an HD image can make it look significantly sharper - enough, perhaps, to make it look like it’s 4K.

Post produce at 4K

Another way you can sneakily bounce your HD material into the 4K domain is to post produce it at 4K resolution. Again, it’s not going to magically capture 4 times the number of pixels but any effects you do will be in 4K. For example, you might want to apply a look or some kind of artistic effect. To the extent that the effect changes the pixels, it will “create” new 4K ones. This isn’t magic: it’s an illusion, but it’s a valid one.

You can also add “clues” to 4K resolution by adding titles. These will be rendered at whatever resolution you set your project to. So if you set it to 4K, your titles will be at 4K, whatever the original resolution of your material.

But, do you know the best way to make your productions look like 4K?

Shoot them well in HD.

To "shoot well" you have to pay attention to quite a lot of things.

For a start, use a good camera

That should do without saying, but it often doesn't. It doesn't matter if the camera says 4K on the tin; if it's not a good camera (which can mean a number of different things) then however hard you try to get everything else right, it's not going to make your HD look like 4K.

Expose correctly

Especially if you're recording to an 8 bit codec, you need to make sure you're using every one of the available bits for distinguishing between light and dark pixels.

Light correctly

Personally, I've never understood the obsession with low light performance of a camera. Just because your device can capture video by candlelight doesn't mean you should skimp on lighting! There's more to lighting than mere quantities of photons landing on sensor elements. There's the direction they're coming from, and the overall contrasts in the scene. If you're going to the trouble of lighting a scene, you might as well do it, you know, brightly.

Use good lenses

If your lenses aren't sharp, then your video isn't going to even look like HD - never mind 4K. And make sure you know how to focus with them: basic, yes; but often overlooked.

Use a smaller sensor!

I know this cuts across what is probably the biggest trend in film making of the last five years, but, honestly, I'd rather get the shot than have to discard sixteen takes because they're out of focus. Shallow depth of field is just one of a multitude of cinematic effects. It's not a panacea and in the wrong place at the wrong time it can be an absolute menace. Any number of times I've captured an image only to find out that the tip of the subject's nose is in focus while their eye lashes are blurred.

Of course big feature film budgets allow for experienced focus-pullers. But if it's just you and a DSLR, who's going to pull focus for you? And without proper cinema-type markings on the lens, it's going to be largely impossible anyway.

It's a good idea to try to record at high bitrates, or uncompressed. You can do either of these if you have the right type of external (HDMI or SDI) recorder. Most external recorders will record to 10 bit ProRes at up to around 220 Mbit/s. It's an edit-friendly format, with every frame encoded individually so there's no dependency on previous frames, and recording in 10 bits gives a significant amount of additional headroom for post-processing, even if your original signal was only 8 bit.

HD rules in the cinema!

There is a camera that pretty much puts all of this (apart from the bit about the small sensor) into practise. How many times have you heard that Skyfall, Hugo or Game of Thrones wasn't sharp enough? Exactly none, I would imagine, even though, with the exception of Game of Thrones, which was made for TV (widely praised for its production values), these films have been seen on the biggest screens and scrutinised by the most critical of critics. Absolutely none have said it's not sharp enough for the cinema.

What this proves, I think, is not only that HD is good enough, but that it can functionally substitute for 4K and no one is any the wiser. There are far more important elements that make up a picture than the sheer number of pixels. Your brain does a lot of the work.

Think about your school playing field, or your favourite park when you were growing up. Zoom in on the grass so that you can see the blades waving in the wind. Now focus on a single blade of grass. Look at the markings, the nature of the edge; how it reacts when it catches the sun.

Were you able to do that? Most people can. It's incredible (literally) when you think about it. And absolutely none of that thought experiment has anything to do with resolution.

As we've said before, if you can acquire in 4K, then do so: it's able to make HD look better when downsampled: turning 4:2:0 into 4:4:4 for example.

But if you shoot in HD in the right way, taking all the steps mentioned above (and some, undoubtedly that we haven't mentioned) then you can put your HD material on a 4K screen, and still enjoy the view.